June 13,

2021 | 6:55 pm

Introspective

By Romeo

L. Bernardo

From May 31 to June 1, thin

power reserves resulted in the National Grid Corporation of the Philippines

(NGCP) raising yellow and red alerts and hours-long rotational brownouts in

some parts of Luzon. Understandably, this episode drew indignation from

consumers and sharp criticism from pundits and politicians.

To me, this very much feels

like déjà vu. On Jan. 27, 2014, I wrote an article (“The way forward for the

power industry,” https://www.bworldonline.com/content.php?section=Opinion&title=The-way-forward-for-the-power-industry&id=82546)

on the then price spikes and the hearings and investigations that ensued. Much

like in 2014, the initial reaction and resulting discourse centered around

short-cut solutions due to an oversimplified understanding of what is a

difficult-to-understand industry. Much of the criticism was directed towards

the Electric Power Industry Reform Act (EPIRA), which is the law passed in 2001

to reform the electricity industry.

I said then that a fair

appraisal of EPIRA could be captured in the common idiom “so far, so good.” Seven

years later, I would now submit that EPIRA, “like fine wine, has grown better

with age.”

When discussing EPIRA, it

is always important to start from the beginning. EPIRA was created to address

long-term structural weaknesses in our power system that accumulated over time

and resulted in crippling brownouts in the 1990s and a ballooning debt burden

for the government. It was likewise meant to introduce competition to bring

down power rates, give consumers more choice, and attract long-term private

capital.

In 2014, I explained that

EPIRA had advanced in the privatization of 80% of government assets. I

mentioned that it had progressed, albeit at a slower pace than envisioned, in

market formation with the Wholesale Electricity Spot Market (WESM) and Retail Competition

and Open Access (RCOA), which has given businesses, and soon individual

consumers, the choice of where they source their power and the ability to get

better rates.

Since then, EPIRA has

recorded more wins. From 2011 to 2020, we have seen a decline in the prices of

electricity in most major markets. In this time period, WESM prices have fallen

by 43%, Meralco generation rates by 16%, and RCOA (from 2017 only) by 17%.

We have seen the entry of

new generation companies (gencos). The sale of assets to the private sector

yielded the government P911 billion that reduced the obligations of the Power

Sector Assets and Liabilities Management Corp. (PSALM), and, more importantly,

unburdened the government from spending to build new plants to keep up with growing

demand.

Now, you may wonder, if

EPIRA has been mostly a success, why are we still experiencing rotational

brownouts? Surely this is not evidence of success. To be clear, EPIRA as a law

laid the legal foundation for a sustainable and competitive electricity sector,

but like any law, it is only effective if we implement it properly, if market

participants play by the rules, and if our regulators enforce the rules

effectively.

By most measures, the

implementation of EPIRA has been incomplete and slow. A clear example of this

is the RCOA Market. It was intended to provide all consumers with the power to

choose their power supplier not later than three years after EPIRA enactment,

but the implementation started only in 2013. Today, 17 years have elapsed and

we have only partially implemented it.

EPIRA’s implementation

requires the private sector to carry a greater role in the mission of powering

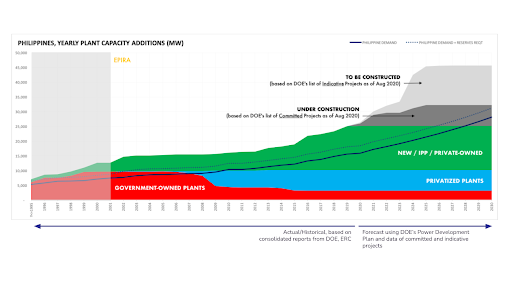

the country. On this front, we have seen a number of shortcomings. First, while

we see significant growth in the generation side of the industry (capacity

increased from 15 GWs in 2003 to 26 GWs in end-2020), we still experience gaps

in power supply. This is primarily because as a fast-growing economy, power

demand is expanding at a pace that gencos are hard-pressed to keep up with. A

contributing factor is that much of our existing generation fleet is old and

thus given to breakdowns.

On the transmission side of

the industry, we have seen bottlenecks in the construction of transmission

lines. On average, transmission lines are three to four years delayed in their

implementation. Without certainty in transmission, generators are unable to

build new power plants. We have also seen that the transmission line operator

has not fully contracted firm power reserves. Where the system operator’s role

is to procure reserves, much like procuring a genset for your home, to call on

in a time of power crisis, it has not procured sufficient firm reserves and so

is unable to faithfully perform its role as an emergency backstop.

Finally, our regulators

play an important role in seeing to it that the rules are properly enforced. On

this front, I can only describe our regulator’s approach as schizophrenic,

where they have tended to over-regulate the competitive part of the industry

and under-regulate the regulated part of the industry.

EPIRA designed the power

generation side to be competitive, and allow competition to yield lower prices

and higher reliability. There are rules in place, including market power

restrictions, to keep any one player from unfairly prejudicing the consumer.

Unfortunately, since then, the regulators have churned out regulation after

regulation to curb the activities of generators. Each regulation is designed

with the consumer in mind, but, as with many regulations and laws, they often

carry unintended consequences that distort the behavior and incentives of

market participants. When investors do not build new plants or do so slowly

because the business environment has been riddled with regulatory uncertainty

and risks, end consumers and our entire economy lose.

On the other hand, the

regulators have fallen short in its responsibility to enforce the rules over

NGCP, which has the monopoly over the transmission lines in the country. NGCP

over the past 10 years has been non-compliant with the rules that require it to

build transmission line infrastructure to ensure that we have the power when

and where we need it, especially during times of power shortage. The

non-compliances come in the form of a lack of transmission lines, a lack of

redundancies in our network, a lack of power reserves, and not meeting the IPO

requirement under the law.

The schizophrenic approach

to regulation is also apparent in the approach to regulating the weighted

average cost of capital (WACC) allowed different market participants. Where

arguably the WACC used by regulators to regulate rates of competitive gencos

should be higher than that of a monopoly, reflecting the higher risk

environment, it is today the reverse. The monopoly (NGCP) earns a higher return

in a market where it has no competitor.

Where do we go from here?

If we want to avoid the power shortages that we just experienced, we need to

first correct our regulatory approach. We have a strong legal and regulatory

framework in EPIRA. Our regulators should focus on enforcing it rather than

adding to it. More specifically, our regulators should focus on regulating the

regulated business of transmission of power and consider simplifying the rules

for gencos to allow the market to work, to de-risk the environment and to

attract more long-term private capital.

In order to ensure that we

have adequate reserves, the regulators should compel the Systems Operator to

contract the full, firm reserve requirement. This can be done within 30 days,

as there are genco offers today sitting on the desks at NGCP. This would ensure

that we have the spare reserves the next time that the supply of power thins.

Lastly, we need to fast

track the implementation of the transmission line network. A three to four-year

year lag creates significant uncertainty and an imbalance in the market.

Correcting this will de-risk the investment environment and will encourage the

entry of more power capacity into the grid.

All in all, EPIRA has come

a long way and has saved billions for consumers and taxpayers alike. Let’s

focus our efforts on making it work.

The views and opinions in

this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the

position of these Institutions.

Romeo L. Bernardo was

Finance Undersecretary during the Cory Aquino and Fidel Ramos administrations.

He is an Independent Director in a major publicly listed conglomerate active in

the energy business and serves as a Trustee/Director in the Foundation for

Economic Freedom, The Management Association of the Philippines and The Finex

Foundation.

romeo.lopez.bernardo@gmail.com