January 24, 2021 | 6:37 pm

Introspective By Romeo

L. Bernardo

SOURCE OF DATA: BSP

SOURCE OF DATA: BSP, IMF

SOURCE OF DATA: BSP

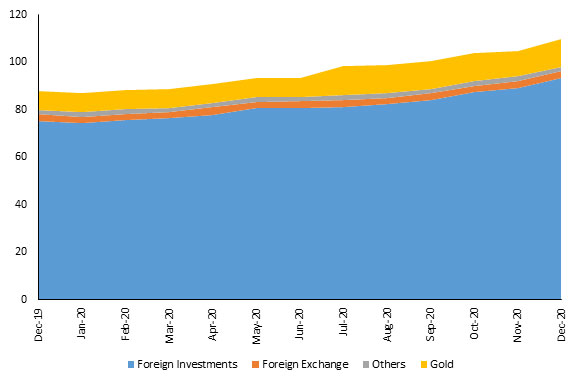

Last year, gross international reserves (GIR) surged 25% to end the year

at close to $110 billion. This is remarkable considering the unprecedented

global scale and severity of the COVID-19 crisis.

While short-term capital exited emerging markets as in past crises, this

time around in the Philippines, the balance of payments (BoP) remained in

surplus and even ballooned to nearly $12 billion in the year to November. The

latter mainly reflects collapsed imports as the economy went into recession

and, as tax revenues buckled, increased government borrowings with the overall

external debt estimated to have risen by around $10 billion last year.

In an interview with the editor of the country’s leading business paper

last week, BSP Governor Benjamin Diokno highlighted this atypical but positive

upshot of the crisis that kept depreciation pressure off the peso and allowed

monetary authorities to aggressively cut policy interest rates. He added that

he expects the GIR to continue growing this year, possibly reaching $120

billion.

OUR VIEW

Pre-pandemic, the Philippines already had one of the highest foreign

exchange stockpiles based on the IMF’s assessment of reserve adequacy (ARA).

The ratio of reserves to ARA at end-2019 was at 2, higher than the 1-1.5 ratio

considered adequate and above most countries’ reported ratios. Last year, the

additional reserve buildup unarguably gave economic managers more wiggle room

to manage the crisis, not least by helping to anchor the sovereign’s credit

rating and giving the government continuing access to international capital

markets at relatively tight borrowing spreads. By the end of 2020, GIR could

amply cover over 5.4x short-term debt plus principal payments on medium to long

term loans due in the next 12 months, up from 3.9x at the end of 2019.

Going by this, the GIR will continue to amply cushion any external shock

in the near term. Moreover, given our dimmer view of the economy’s growth

prospects, we think the current account will still register a modest surplus

this year with moderate import growth, while private capital outflows are

unlikely to be as massive as last year, with portfolio flows starting to return

in 4Q20. We note too that although GIR was in large part boosted by increased

government borrowings, these consisted of long-term loans, a significant

portion of which is owed to official creditors who also provided long grace

periods on principal repayment. One downside risk given BSP’s (Bangko Sentral

ng Pilipinas) decision last year to actively trade its gold holdings, is lower

gold prices.

However, holding excess reserves is not without cost. From a

consolidated public sector viewpoint, the collateral value of these highly

liquid assets needs to be weighed against the negative carry associated with

their low returns as well as foregone productivity-enhancing domestic public

investments. As pandemic risks subside with improved health management and the

promise of vaccination, one could argue that keeping such high precautionary

cash is no longer warranted.

Too, with the peso having appreciated by 5% in real, trade-weighted

terms last year, many in policy circles would argue for a more proactive

government response to support the export sector. Realizing that the BSP could

only do so much with its foreign exchange market interventions, the suggestion

is for the government to perhaps forego external commercial market borrowings

altogether. As the argument goes, at a time when the government is looking to

pass more of the burden of spurring economic growth to the private sector, raising

the purchasing power of dollar earners, particularly overseas and BPO workers,

will help significantly in reviving domestic consumption which accounts for

about 70% of GDP. Government may also fret less about the impact on domestic

interest rates of more local borrowings considering last year’s aggressive

monetary easing that injected close to P2 trillion of liquidity into the

financial system, weak loan market (both demand and supply), and a two-year

window to directly tap an additional P280-billion loan from the BSP.

There is thus scope for the government to nudge the GIR down this year

rather than allow it to climb some more. For now, there are no signals that it

intends to do so.

Romeo L. Bernardo was finance undersecretary during the Cory Aquino and

Fidel Ramos administrations. This column was a post to subscribers of

GlobalSource Partners (globalsourcepartners.com) a New York-based network of

independent analysts. He and Christine Tang are their Philippine partners.

romeo.lopez.bernardo@gmail.com